Search results for "haavikko"

The power game

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

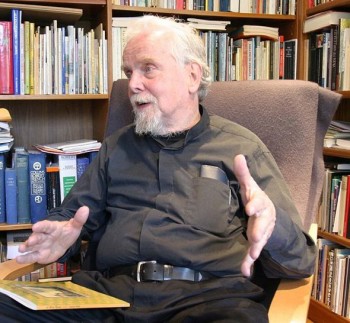

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

This week, a cluster of pieces from and about left-leaning Tampere, the ‘Red City’ of Finland

The Tampella and Finlayson factories, 1954, Tampere. Photo: Veikko Kanninen, Vapriikki Photo Archives / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also known as the ‘Manchester of Finland’ for its 19th-century manufacturing tradition, Tampere – or rather the suburb of Pispala – produced two important, and strongly contrasting, writers, Lauri Viita (1916-1965) and Hannu Salama (born 1936). Both formed part of a group of working-class writers who emerged after the Second World War, many of whom had not completed their school careers and whose confidence arose from independent, auto-didactic, reading and study.

To understand the place from which these writers emerged, it has to be remembered that there is more to Tampere than a proud radical tradition. As Pekka Tarkka remembers in his essay, the Reds were the losing side in the Finnish civil war of 1918, and for years afterwards they formed ‘a sort of embattled camp in Finnish society’. History is always written by the winners, and authors like Viita and Salama played an important role in giving the Red side back its voice.

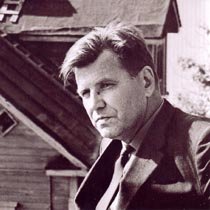

Lauri Viita.

Lauri Viita celebrated Tampere by offering an image of it that is, as Tarkka remarks, ‘poetic, deterministic and materialist’. His poetry differed sharply from the modernist verse of contemporaries such as Paavo Haavikko and Eeva-Liisa Manner, both of whom we have featured recently in our Archive pieces, which abandoned both fixed metres and end-rhymes. His work was an often heroic celebration of the ordinary life of proletarian Tampere, and the more traditional form into which it breathed new life made it accessible. My own mother, for example, who had grown up the child of a Red working-class family far away to the north, in Kajaani, steeped in the rolling cadences of poets such as Aaro Hellaakoski and Uuno Kailas, never really got the hang of Haavikko, or Manner; but she loved Viita.

Here we publish a selection of Viita’s poems, translated by Herbert Lomas, who does an excellent job of capturing his easy-going, unselfconscious rhythms. The introduction is by Kai Laitinen.

Hannu Salama.

Photo: Ptoukkar / CC BY-SA 3.0

Salama is a far more politicised writer than Viita, and he is writing about a Tampere that is already in decline. In his major work, Siinä näkijä missä tekijä (‘No crime without a witness’, 1972), he writes about the travails of the communist minority, doomed to slow extinction – the same band of fellow-travellers to which my grandfather in Kajaani belonged. My mother wasn’t a Salama fan, though – I think his Tampere wasn’t beautiful, or heroic, enough. As someone who had moved far away, to England, she wanted to celebrate, not to mourn.

Here we publish a short story, Hautajaiset (‘The funeral’), which was written at the same time as Siinä näkijä missä tekijä. It’s an unvarnished account of a Tampere funeral which is, at the same time, the funeral of the old, radical way of life – which, sure enough, has vanished almost as if it never existed. As Pekka Tarkka writes of Salama’s short story and the revolutionary songs which run through it: ‘There will be no more singing of communist psalms, or fantasies of the family and of the revolutionary spirit.’

As Marx didn’t say, all that seemed so solid has melted, irretrievably, into air.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 380 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Men and a woman, too

7 November 2009 | This 'n' that

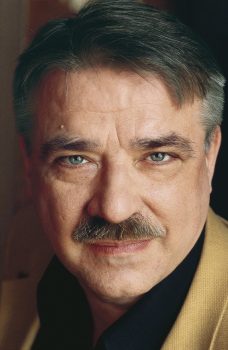

In October, according to the best-seller list (Mitä Suomi lukee, ‘What Finland reads’), the top seven non-fiction titles included biographies of four Finns – an industrial tycoon (Pekka Herlin, one-time director of the Finnish Kone elevator company), a poet (Paavo Haavikko), and a former Prime Minister (Paavo Lipponen).

In October, according to the best-seller list (Mitä Suomi lukee, ‘What Finland reads’), the top seven non-fiction titles included biographies of four Finns – an industrial tycoon (Pekka Herlin, one-time director of the Finnish Kone elevator company), a poet (Paavo Haavikko), and a former Prime Minister (Paavo Lipponen).

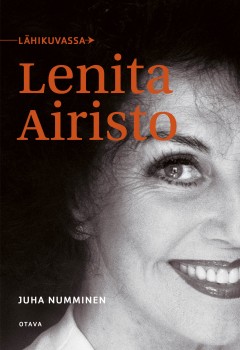

The seventh place was held by a book on a woman: Lenita Airisto, winner of a 1950s beauty contest, later a television hostess, celebrity, writer and businesswoman (Lähikuvassa Lenita Airisto, ‘Lenita Airisto in closeup’, by Juha Numminen).

The Finnish fiction list was topped by the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Isku ytimeen (‘Strike to the core’). Then came Kjell Westö’s novel Älä käy yöhön yksin (‘Don’t go out into the night alone’, a translation of the Swedish-language original, Gå inte ensam ut i natten) and Jari Tervo’s Koljatti (‘Goliath’). The latest Henning Mankell was number one on the translated fiction list.

Speaking about the heart

30 June 1991 | Archives online, Articles

New Finnish poetry, translated and introduced by Herbert Lomas

The ‘modernist’ revolution in Finnish poetry is now 40 years old, and the art must be ripe for changes.

Of course, the modernism of post-war Finnish poetry was not – except in Haavikko and to some extent in Saarikoski – extremely modernist. The poets were more interested in their content than their experiments. They were perhaps closer to ancient Chinese poets and early Pound than to Eliot in their elided brief juxtapositions and meditations on nature, society and moment-to-moment transience. The poets picked up a few liberties that unshackled them from metrical and rhyming formalities uncongenial to Finnish stress, syntax and phonemics; and they took off to speak about the heart. That is the strength of this poetry, and its originality, since all originality consists in being oneself – which includes one’s national self, and ultimately other people’s selves. And every generation still has to make a new start, admittedly in new circumstances, with the experience of its forefathers from birth to death. More…