On Heikki Turunen

Issue 1/1977 | Archives online, Authors

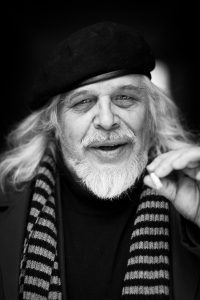

Heikki Turunen.

Photo: Heikki Turunen

Since the 1960s the social and emotional problems caused by the shift of population from the country to the towns have been one of the predominant themes of the regional novel. But while novels on this subject are seldom lacking in sociological interest, the quality of the writing is not always very high. Two writers whose work does stand out are the late Timo K. Mukka, whose novels are set in Northern Finland, and Heikki Turunen (1945– ), who writes about North Karelia. The latter is the part of Finland that has suffered most acutely from the mechanization of traditional occupations and the ensuing depopulation as people have been forced to seek new sources of livelihood either in Southern Finland or in Sweden.

Heikki Turunen grew up in a remote backwoods area of North Karelia where his father had a smallholding. After leaving school he worked for a time as a journalist on a local newspaper and saw for himself the misery caused by depopulation. His first novel, Simpauttaja (‘The Dabster’, Werner Söderström 1973, published also in Swedish by Raben & Sjögren in 1976: Livaren) became a best seller on the scale of the major works of Mika Waltari and Väinö Linna, despite the fact that it is very local in content and is written in broad North Karelian dialect. The novel is set in Turunen’s home area, which is seen through the eyes of a young man attempting to come to terms with the disintegration of the traditional way life. The author’s second novel, Joensuun Elli (‘Elli of ]oensuu’, Werner Söderström 1974), examines similar problems of adjustment seen from the point of view of town dwellers. Turunen’s works combine irrealism and total, often brutal realism to portray the conflict between town and country, the exploitation of the natural resources of North Karelia, the destruction of the traditional way of life. The old, the sick, the infirm and the other human casualties are left behind. The rest depart. The few young people who remain do so against their will because they have neither the means nor education to leave. At the same time, Turunen shows how those who succeed in escaping to the cities build fantasies about the countryside they were once so glad to leave. In Kivenpyörittäjän kylä (‘The stoneroller’s village’, Werner Söderström 1976), as in his earlier novels, Turunen presents a series of situations in which mass urban culture clashes with traditional rural values. With wry humour he depicts the efforts of the country people to adopt an urban culture, assuming habits of dress and speech which do not come naturally to them. The book describes how a family of Finns who have settled in Sweden return to their old village in North Karelia for a short holiday. The village, Jerusalem, is in a state of decay: houses, farms and shops have been abandoned, the school is empty, and everything built after the war in the hope of a better future is falling into dereliction. Only one young man is to be found in this village of the sick, the infirm and the elderly: he is a half-witted giant, a kind of Sisyphus, endlessly trundling a huge stone up and down the village street – a clear symbol of the futility of all the work done by the North Karelians after the last war to develop land for agriculture by cutting down trees and clearing away stones. The extract below brings out the theme of the novel. Village dances were traditionally occasions when young people would meet each other and choose their marriage partners. In this scene the bride is no longer young and has had an operation that makes it impossible for her to bear children. One of the wedding guests kills himself at the party and the next time the villagers meet, it is for his funeral.

Tags: agriculture, countryside, Finnish history, Karelia, novel

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

-

About the writer

The Finnish literary theorist, historian and professor Hannes Sihvo (1942-2003) began his career by writing the history of the Kalevala Society Foundation. He later wrote several works on the history of Carelia and Ingria while teaching at the University of Joensuu. He was also the chair of the Aleksis Kivi Society from 1997 to 2002.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.