On Matti Pulkkinen

Issue 2/1978 | Archives online, Authors

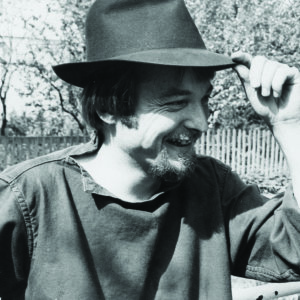

Matti Pulkkinen. Photo: Gummerus

Matti Pulkkinen’s grandfather was born in 1842 in a forest village close to the Russian border, in an area which could only be reached by water. When he grew up he became a tar-burner, a traditional occupation in north-east Finland. Pulkkinen’s father worked for the Otava Publishing Company in the early years of the present century, a time when ordinary Finns were beginning to show a real interest in literature. In his home in one of the most remote parts of North Karelia, he assembled a library which ranged from Mark Twain to the detective stories of G. K. Chesterton. He was 70 when his youngest son, Matti, was born in 1944. Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche were the two writers whose works did most to stimulate Matti Pulkkinen’s enthusiasm for literature. After leaving school he set out to see the world. He worked as a lumberjack, a primary school teacher, a statistics clerk in a gynaecological hospital, a bank teller, an accounts clerk, and later as a carpenter, took part in the restoration of the medieval church at Vanaja. From 1969 to 1971 Pulkkinen worked as a nurse in mental hospitals in Frankfurt, West Berlin and Bern. While in Switzerland he became interested in Jungian psychology and modern group therapy.

Pulkkinen’s novel, Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’, Gummerus), published in 1977, was awarded the J.H. Erkko Prize for the best first novel of the year and the Kalevi Jäntti Memorial Prize. It rapidly became a best seller and has already had two reprints.

Ja pesäpuu itki contains several ironical descriptions of ‘sensitivity training’ sessions. Pulkkinen believes that group therapy can contribute much to the participants’ self-knowledge and improve communication, but it can also merely be a waste of time and even damage the patient’s health. Nor does Pulkkinen have a high opinion of the modern mental hospital. His novel has been compared to Ken Kesey’s One flew over the cuckoo’s nest: both are about people who find themselves caught up in the treadmill routine of a mental hospital where the staff is interested only in turning them into well behaved patients. Kesey showed how North American Indians and the Irish Americans rebelled against those who tried to force help upon them. Pulkkinen’s characters, the North Karelians, also represent a minority at the periphery of society, one that has lost its roots as a result of the sudden and rapid change in the traditionally agrarian way of life.

In Pulkkinen’s novel the hospital and group therapy sessions, which take place in the present, are set in the context of the past, which is depicted in great detail. The novel describes a period of three generations, which the ancient North Karelian village structure disintegrated and the Karelians were sucked up into the turmoil of urban life. The representative of the first of the three generations is Ukko Suutarinen, a patriarchal and almost legendary figure. His heirs dissipate the family wealth and sell their forests. They are caught up in the war, the traditional harmony of the village community is shattered and people who have lived together go their separate ways; farms are neglected, buildings fall into disrepair and families degenerate. The principal character of the novel represents the present generation. He approaches the secrets of life like a detective and concludes that the real cause of suffering in modern society is the recurrence from generation to generation of the conflict between two social groups – the old, powerful families and the weaker members of the same community.

The action in Pulkkinen’s novel moves backwards and forwards in time.

One of the book’s most remarkable episodes describes a battle of wills between Ukko Suutarinen and the old woman Kareinen, a folk healer, who represents the poor and oppressed members of the community. It takes place on a massage bench in an old smoke sauna. Another is the balladlike account of the love of two members of a later generation.

Ja pesäpuu itki is more than a history of people caught up in the turmoil of social change. Pulkkinen’s ability to see the changing structures of society through the eyes of his characters – both the balanced and the unbalanced – is outstanding. Pulkkinen does not idealise the past.

Through his principal character he puts forward the theory that we can find our own identity in modern society only by coming to terms with the mysteries of the past.

Tags: novel

1 comment:

Leave a comment

Also by Pekka Tarkka

Tellervo Krogerus: Sanottu. Tehty. Matti Kuusen elämä 1914–1998. [Said. Done. The life of Matti Kuusi, 1914–1998] - 22 May 2014

In good company - 18 October 2013

Nationalism in war and peace - 3 May 2012

In memoriam Bo Carpelan 1926–2011 - 24 February 2011

Arne Nevanlinna: Hjalmar - 5 November 2010

-

About the writer

Pekka Tarkka (born 1934) is an author and literary critic. Among his works are an extensive biography of the poet and writer Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) and of the author Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934; first volume, 2009; the second volume, 2012).

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.

8 June 2018 on 7:55 am

eagerly waiting to read Matti Pulkkinen’s Novel.