Fairy tales of a journalist

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Authors

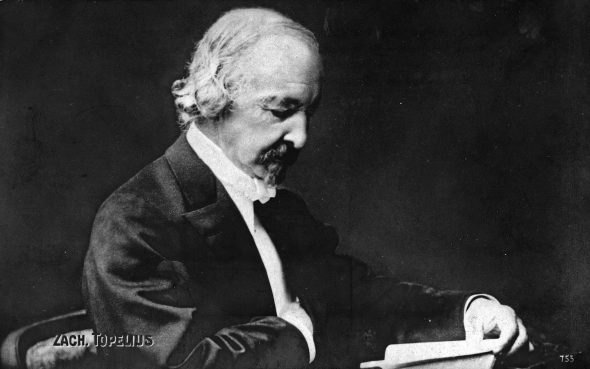

Zacharias Topelius. Photo: SLS

In 1918, Selma Lagerlöf, the Swedish novelist and recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature, was commissioned by the Swedish Academy to write a book on the life and works of Zacharias Topelius, in celebration of the centennial of his birth. As she says in the introduction to her Zachris Topelius of 1920 (where she uses the familiar contraction of the great man’s given name), she realized that she was up against the monster work-in-progress of Valfrid Vasenius, which had already reached three volumes and which would not be finished, with six, until 1930.

Lagerlöf jotted down her almost novelistic account of Topelius’s first thirty-eight years, from his birth in Ostrobothnia, as the son of a country doctor with strong folkloristic interests, to the appearance of his major patriotic poem of 1856, Islossningen i Uleå älv (‘The breakup of the ice in Uleå river’), filled with hopeful thoughts about an independent Finland. It can be reckoned that more people have enjoyed Lagerlöf’s chatty pages than have struggled with Vasenius’ positivistic monument, and that a common notion of Topelius, influenced either by Aunt Selma or schoolteachers who have partaken of her burbling spirit, is that of a man too good and emotionally too limited to be great.

Today, he seems a paler Walter Scott: in his historical narratives, there are plenty of stormy nights and secret passages and sudden rescues, but, unhappily, no masterful portrayals of character – no Dandie Dinmont, no Jeanie Deans, no Andrew Fairservice. Or he is an indefatigable singer of sweet songs. Or he is a dramatist whose historical plays lie buried in the annals of Finland’s theatre, but whose fairy-tale playlets may still be acted – willingly or not – by Finland’s long-suffering school-pupils. Or he is a pleasantly avuncular teller of innocuous tales for children, which no longer have the international celebrity they possessed in great-grandfather’s day, notwithstanding the claims made by Topelius enthusiasts, to the effect that they rival or sometimes even surpass those of Hans Christian Andersen.

Or, dimly remembered, he is a journalist of some stature. To be sure, Finland’s public mind cannot be blamed for knowing the newspaper work of Topelius mostly by hearsay; the corpus is substantially inaccessible, unless one wants to curl up with microfilm from the golden age of Topelius’s newspaper of 1842-60, Helsingfors Tidningar. As the editors of the twenty-five volumes of Topelius’s collected works (1904-1905) told their readers: a ‘selection of these extremely remarkable essays’ had at first been planned, but, in order to be representative, it would have become ‘too large,’ and so the editors concluded that nothing was better than something. A series of retrospective essays from another Helsinki Swedish-language newspaper, Finland (1885), eventually did appear in book form, in Finnish as a part of an edition of Topelius’s works in 1932 and, in the original Swedish, as Anteckningar från det Helsingfors som gått (‘Sketches from the Helsinki that has passed’) in 1968; but the volume is small consolation for the Topelian friend who likes to enjoy journalistic wit in armchair comfort.

Finland, to be sure, maintains an ingrained affection for Topelius, a sentimental attachment as though to an elderly relative or family friend. In Sweden, where Topelius was king of the literary-popularity market, once upon a time, he has been stamped (by a judicious professor of literature) as a harmless but faded representative of the late Biedermeier, and his letters from his old age have served as a mine for unpleasant remarks about Strindberg: to the publisher Bonnier (from whose stable Topelius threatened to withdraw, unless Bonnier broke with the immoral Swede), he wrote: ‘I have heard too much about The Son of a Servant Woman – from impartial readers, too – to want to soil my hands by touching the book.’ Yet, some could wish a better fate and greater interest for Topelius, this extremely moral man, even at the cost of scouring his works for elements that make him seem a little less the paragon. And some could guess that the very parts of his work which are the most vital today, the ‘fairy tales’ and the news paper writing, are also the most likely to reveal his ambiguities.

Topelius’s careers as an active journalist and as a teller of children’s tales began almost at the same time. His series of causeries, the Leopoldinerbrev (‘Leopoldine letters’), feigned epistles about Finnish conditions to a Lieutenant Leopold, a Finlander on the Tsar’s service in the Caucasus, and then to a Miss Leopoldine, resident in Sitka, Alaska, began in January 1843; and the first collection of his tales for children, the Sagor, appeared in 1847, with pictures by his wife, to be followed, as in the case of Andersen’s Eventyr, fortalte for børn (‘Tales told for children’), by other collections over the years, and occasional publications in albums and annuals. In 1865, Topelius. began to use a new title, Läsning for barn (‘Reading for children’) and maintained it until an eighth and last reader in 1896, two years before his death; the best of all these tales were then included in the eight volumes, also called Läsning for barn, appended to the collected works mentioned above. Of course, they had long since been translated into Finnish, and so had made their way to the majority of Finland’s young readers, or those read to.

A student of these two parallel actions – the one, for adults, pretty well ending in 1860, the other, for children, continuing throughout Topelius’s career – has to be impressed by the practical tone, the good sense, of what Topelius says, to the one audience as to the other. As the detail work in the historical narrative repeatedly proved, Topelius loved the past and its apparently wholesome simplicity. But he was aware that the idyll could be uncomfortable or downright dangerous. In Helsingfors Tidningar for 1858, there appeared an article from his hand which lifted a veil from elementary miseries of life: ‘Is there a single larger building [in Helsinki], save the public bathhouses, which has even the slightest trace of water conduits? How many people could be spared the promenade, so barbaric in our climate, to an outhouse in the wintertime?’ Or Topelius could discuss the housing shortage: it had existed even before the Crimean War, and now it had come acute. What quarters there were cost too much: ‘Can a man pay a third or a fourth of his salary for bare walls?’ Here, he sympathized with the capital’s large group of civil servants; but the poor were even worse off: ‘A very small part of the working class in Helsinki owns its homes; some of its members dwell above the ground in little wooden huts, and some below’, in cellars. Hard and practical truths indeed!

Likewise, the tales tell their little readers not to be proud (the message of the first of them, ‘The church-cock’) but rather humble (‘Adalmina’s pearl’), not to submit to peer pressure (‘A heart of elastic rubber’), not to be vengeful (‘Bullerbasius’), to be generous (‘The merciful man is rich’), to overcome cowardice (‘The fortress hero-hall’), to be loyal to home ground (‘Pikku Matti’). Fredrik Böök, the biographer of H.C. Andersen, claimed that Scandinavian children were given a special social awareness, almost with their mother’s milk, by hearing such tales as The Little Match Girl; could not much the same pedagogic claim be made for Topelius as the creator of the necessary basis for a true democracy (however long the realization of that democracy in Finland then took)? And could it not be argued that he had given adults equivalent les sons? A melancholy wag might propose that it was too bad for Finland when ‘The tales of Ensign Stål’ of Runeberg, with their stoicism and their heroic deaths, clad in hypnotizing rhetoric, and not Topelius’s ‘Leopoldine letters’ and their paralipomena – witty, civilized, liberal, light of touch – became an ornament of every bookshelf. Yet the same wag could be thankful for the blessing of the children’s tales.

Of course, the tales contain elements that, to modern sensibilities, are upsetting – for example, the implicit anti-Semitism of the portrait of the villainous and big-nosed Guldberg, and his loathsome son Moses-Mosep, in ‘Forest-bear’; or the rather tiresome emphasis on ‘our Lutheran faith’; or the contempt for learning (as opposed to the vigorous life) that can be read, or misread, out of ‘A learned lad’, with the comical milksop Hegesippus and the out-of-doors boy, Knut (who may, to an American reader, have the features of a juvenile John Wayne), and out of ‘Little genius’, with its equally comical learned man. These stories are particularly insidious because of their inventive verbal humor; we may hope that their lessons, all too effectively presented, have had nothing to do with Finland’s endemic halterophilia. But who knows? Have not all Finns been made incorrigibly honest by early contact with Topelius’s ‘The poor box?’ Just so, in the journalism, a contemporary reader will grow uneasy at Topelius’ pussy-footing where Finland’s Russian masters were concerned; his circumspection and, at times, his outright worshipfulness stand at odds with the clear glances he can give to social and cultural matters. Yet, the censorship of the time must be borne in mind, and the fact as well that Topelius, at once a patriot and an optimist, sincerely believed in the benevolence of Russian rule.

Looking at the journalistic work done for Helsingfors Tidningar, it was a remarkable accomplishment: the maintenance of so high a standard of lucid thought, convincing fairness, and brilliant style, over such a long period of time, is unique in the history of Nordic letters. As for the tales, they must forever be compared to Andersen’s, reviewed by Topelius in his newspaper in 1846, and inspiring his own efforts. Now, is Topelius genuinely worthy of mention in the same breath with the great Dane, or is he simply a cleverer, more supple version of the humane moralizer from Sweden, ‘Uncle Adam’ (C.A. Wetterbergh, 1804–1889), the physician whose tales for children Topelius so much admired? Topelius’s tales apparently lack the problematical nature of some of Andersen’s masterpieces – the sexual cruelty hinted at in The Collar, the terror that runs through The Shadow, the sense of an end of the world that hangs over The Dock Leaf. Yet there are instances where Topelius has a dark side matching Andersen’s: for example, in ‘Princess Lindagull’, with its tragic villain Hirmu, or in ‘The brownie in Turku Castle’, whose immortal curmudgeon has some very discouraging things to say about mankind’s fate, or in ‘George’s kingdoms’, about the death of promise.

It may be that there are, in truth, realms where Topelius can best Andersen in his portrayal of natural disaster (‘A mighty lord’s hunting-dog’), in his portrayal of a fantastic land which nonetheless is real (the wonderful Lappish stories, ‘Sampo Lappolitt’ and ‘Star-Eye’), and in his portrayal of the transitoriness of life, as in ‘The old cottage’. A chill should go through the reader when he or she comes to the coda of that story, whose main figure, the girl Marie, has grasped the nub of ageing and of death: ‘In seventy years, a great city will stand here with ships and factories, and at this very spot there will be a little gazebo with a pennant at its top, and bright-red silk curtains. Then no one will remember any longer that a cottage once stood here, in which good and happy people dwelt … ‘ Marie’s reveries are interrupted by the cries of her thoughtless friend, Antonie: ‘ “there are the most beautiful, reddest, most delicious raspberries growing here! See how they shine! Notice how they smell! Oh, I don’t know of anything more wonderful on earth than really big, clear, dark-red raspberries. Don’t you agree?” “Oh yes, yes, let’s pluck them,” said Marie, and smiled. ‘The last sentence may not be just consolatory embroidery: ‘And in this innocent merriment, childhood-fresh and sweet, both past and future disappeared.’

Tags: children's books, classics, fairy tales, journalism

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by George C. Schoolfield

Life as an outsider - 30 September 1988

Poetry and Patriotism - 31 December 1985

A portrait of Elmer Diktonius - 30 June 1982

-

About the writer

George C. Schoolfield is professor emeritus of German and Scandinavian literature, Yale University. He is an author, editor and translator of numerous books, among them A Baedeker of Decadence. Charting a Literary Fashion, 1884–1927 (2003) and A History of Finland’s Literature (1998). Schoolfield has written articles and books on Rainer Maria Rilke and on Swedish and Finland-Swedish writers including Selma Lagerlöf, Elmer Diktonius and Edith Södergran.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.