Beyond good and evil?

Issue 2/1987 | Archives online, Authors, Interviews

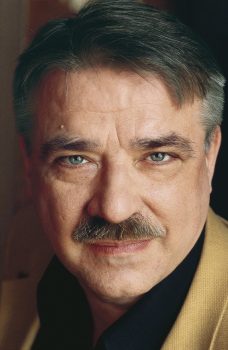

Esa Sariola. Kuva Irmeli Jung

Markku Huotari interviews Esa Sariola

A stylish restaurant in the Stock Exchange building in Helsinki. Esa Sariola and I order a businessmen’s lunch. We talk about hard-nosed success stories. About technocracy, casino economics.

About profit.

A steely-eyed businessman enters the room from the stock exchange and sees us two soft-talkers, even if we look like men, wasting time. The ruthless gambler bolts down his lunch and disappears to the upper floor again, where he is making money.

We remain.

We’re just talking.

And there’s no money accruing in our wallets.

All the same we have a grip on that investor. Esa Sariola has already laid siege to people like him in three books: Väärinkäsityksiä (‘Misconceptions’, 1983), a collection of short stories, and two novels: Rakas ystävä (‘Dear friend’, 1985) and Kuolemaani saakka (‘Until my dying day’, 1986).

Sariola speaks of their killer’s instinct: they know what they are after, and they get it; if they encounter resistance they are prepared to walk all over it.

Not unexpected talk. But then:

‘All the same, they are people like the rest of us, love their children and their wives and family,’ says Sariola.

‘And other people aren’t necessarily any better,’ he adds.

These are not words one would expect to hear from a Finnish author’s mouth. This is precisely the point at which Sariola differs from the main flow of Finnish literature. The difference is both thematic and literary. Perhaps it is also the reason for the attention his novels have attracted.

Winners and losers

Finnish literature is the history of losers. Historical epic and social realism tell of victims who, in the novels, receive justice while the winners are condemned.

Sariola’s novels do not contain that ethos, and evil – the expression is the reader’s, not the author’s – gets its reward: a profitable investment.

‘It would be wrong to say that I consciously set out to write about the problem of evil. Visa, the main character in Rakas ystävä, and Erkki in Kuolemaani saakka are primarily after power and success. They want good things for themselves and organise themselves and others in order to achieve their own goals. Only later does the question arise of how far you can go to get what you want,’ comments Sariola.

‘Visa and Erkki are successful businessmen, but everyone, after all, has to make the same decisions: how and to what extent one can exploit other people. Or, looking at history, the White general in the Civil War and commander in the Winter and Continuation Wars, Marshal Mannerheim, is a scoundrel to some people while to others he is Finland’s saviour.’

‘In the Continuation War President Ryti promised to the Germans that Finland would not make a separate peace with the Russians and got arms in exchange, which enabled the Finns to halt the big Russian attack. Ryti did not consult Parliament about the matter, which meant that, weapons or no weapons, Finland was able to conclude a separate peace. In other words, Ryti cheated the Germans, the Russians and Parliament. Some people believe his action was heroic, others that he was a war criminal.

‘In other words, the same act is right in some people’s eyes, wrong in others’. And that is always the case when you decide something and also put that decision into practice.’

Finland in the 1980s

Sariola’s short stories and novels are set in the present and the future, but the background is clearly Finland in the 1980s. It is very different from the agrarian Finland of the past or even recent industrial Finland.

‘I am concerned with the post-industrial age. Farming and traditional industrial work decline as trade grows. Old social groupings vanish, and in order to succeed people have to move, make quick contacts, be able to manipulate others.’

Sariola believes that even ten years ago it was not possible to write this kind of book. A couple of exceptions come to my mind: one is Paavo Haavikko’s nonjudgmental portrait of a Civil War profiteer, Yksityisiä asioita (‘Private affairs’, 1960). More recently, Olli Jalonen’s Hotelli eläville (‘A hotel for the living’, 1983; see Books from Finland 2/1984), described a woman scientist who has sold her ideals to international trade; but in Jalonen’s case the author’s moral stance is plain.

‘In 1980s Finland people do not necessarily experience society or their own attitudes through any background social group or ideology. They just see a board game, situations, and then work out how they can come out of it the best.’

Borderline cases

Visa in Rakas ystävä does just the same. He hits hard times and causes destruction – but succeeds in personal terms, and even gets his beloved wife Tuuli back.

Doesn’t that kind of person generally fare badly in literature?

‘Because Visa succeeds, a number of people have accused me of a lack of morality. They say that that kind of stone-faced exploiter should at least have a miserable private life. But life’s like that. And when evil is rewarded by good, it is more effective literature.

‘My job as a writer is not to judge, but to describe, to examine people.’

Sariola often uses the term ‘borderline case’. In his novels these include bribery, corruption, speculation, sexual subjugation, violence, murders, the economic and psychological exploitation of religious feeling… sometimes the plots skirt the fringes of credibility.

Although Visa and Erkki are skilful players, there comes a point where their grip weakens. For Visa that moment comes towards the end of Rakas ystävä, when his wife Tuuli returns to him in spite of everything: when everything has been achieved, even love what then?

Erkki, in Kuolemaani saakka, also experiences happiness, and although the end of the book is tragic, a devilish question hangs in the air: is the tragedy of Erkki’s wife and son, in the end, a stroke of luck for Erkki?

Through the impossibility of the extreme situations and resolutions of the novel glints a certain black humour. Of the writers who have dealt with the so-called problem of evil, Eira Stenberg’s work Paratiisin vangit (‘Prisoners of paradise’, 1984) hints at the same matter, perhaps even more eloquently.

Narrative without Judgement

Although the game is hard, Esa Sariola’s language is composed and neutral. His style reflects a lack of inclination to judge. Structurally, the novels progress from one quickly developing situation to another. The explanation is not merely the world in which the writer lives.

‘I have used some of the techniques of crime writing, but mine, of course, are not really thrillers. I think you can use quickly changing scenes to switch the perspective from one person to another, just as if each chapter consisted of a monologue with the speaker’s name at the top.’

No exact dates are given in the novels, no accurate times.

‘Perhaps times are an attempt to see what is happening and what is coming up. I don’t see any sense in writing straight records. Tape-recorder prose – what function could it possibly have? From the point of view of building characters, the use of chronological time would seem artificial to me. After all, people’s consciousness doesn’t work like that. The past, the present and the future are all mixed up, that’s an old truth, isn’t it?’

Sariola the psychologist

It is time to finish our businessmen’s lunch at the Helsinki Stock Exchange, for Sariola has to get back to work at the Hesperia hospital, where he has participated in planning a care scheme for schizophrenic patients. An attempt is made to release patients from the institutional circle so that they may learn to live with their illness in society. Esa Sariola, psychologist, writes about the subject together with Assistant Professor Markku Ojanen in their study Skitsofrenia. Laitoskierteestä vapauteen (‘Schizophrenia. From institution to freedom’, 1986).

To the obvious question, where does he get the subject and characters he writes about, he answers that, for certain, they do not come from the hospital:

‘If my books contain anything about hospitals, it is at most that a hospital is a big organisation like any other, with its own power relations.’

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: short story

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Markku Huotari

Business as usual - 30 June 1994

A poet of the fresh air - 30 June 1987

Chill climates - 30 June 1984

-

About the writer

Journalist Markku Huotari (born 1953) is News Editor at Alma Media Corporation, Tampere.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.