Becoming Finland

23 May 2013 | Reviews

Imaginary heroes: the title page of En resa i Finland. Illustration by C.E. Sjöstrand (1828–1906)

Zacharias Topelius

En resa i Finland

[A journey in Finland (1873)]

Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2013. 173 p., ill.

Utgivare [Editor]: Katarina Pihlflyckt

ISBN 978-951-583-260-3

€38, hardback

(Stockholm: Atlantis förlag, 2013. ISBN 978-91-7353-616-5)

The birth of Finland as a country came as a surprise to those who lived there.

It was created by Napoleon and Alexander I, becoming a reality following Russia’s victory over Sweden in the so called Finnish War. In 1809 Alexander exalted Finland as ‘a nation among nations’, however the new nation still needed to feel like a nation. The Russian rulers supported gentle and non-political nationalism in Finland, in the hope that it would mentally distance the country from Sweden. In this tranquillity, the sense of community they had envisioned grew in Finland.

For this, there were three key factors, all of which stemmed from the 1830s. Elias Lönnrot published the Kalevala, the national epic, proving that Finnish mythology and culture did indeed exist. The poet J.L. Runeberg (who would later become known as the national poet) gave Finland an appearance that was an ideology. He depicted a poor, pious and simple people, a harsh and beautiful wilderness, and with his poems he described the Finnish War, that Finland had lost, as a heroic battle of the people, fought for Finnish values.

The Hegelian philosopher J.V. Snellman (later the national philosopher) started a battle to replace Swedish with Finnish as the language of administration and culture in Finland. As a result of all this, there was material for a Finnish identity and nation. What was needed now was a propagandist who could capture the attention of the people. This role was taken on by the versatile Zacharias Topelius (1818–1898). As a young man, he brought new life to journalism in Finland. Later he became an author of novels, poems and fairy tales, eventually becoming professor of history at the University of Helsinki.

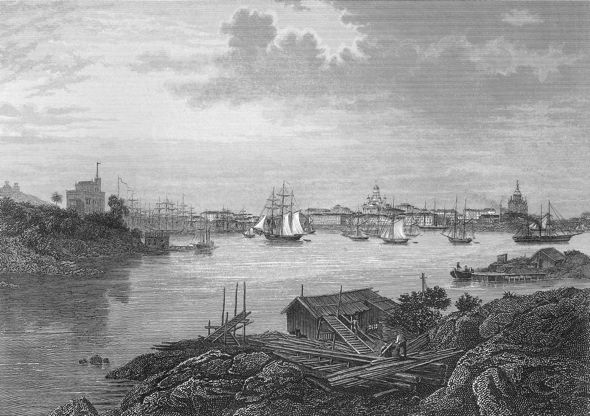

Helsinki harbour, B. Reinhold (1824–1892)

Topelius had a clear message to spread. It had to do with what Finland was, and the importance of national unity. The second half of the 19th century was a time of expansion in Finland’s history; modernisation and industrialisation had begun. Railways were being built and the major Saimaa Canal project, linking the interior of the country with the Gulf of Finland, was completed. The population’s mobility, both geographically and socially, increased. The small towns grew, and there was a desire for an ideology that could explain what the essence of Finnishness was: what should be conserved amid the changes taking place.

Not surprisingly in this period of change, Topelius built his success on a conservative world view. He was strictly religious and idealised old fashioned rural life, assuming Runeberg’s devotional attitude to Finnish nature. However Topelius was also a man of compromises. He bowed without doubt to St Petersburg, and mediated in rows between the Finnish and Swedish speaking populations. As a historian, the idea that Finland was a natural entity, and that this would eventually override the differences between the different groups of the population, was central. This was how a unified people would be created.

Topelius’ most important tool for spreading this well received ideology was Boken om vårt land (in Finnish, Maamme kirja, ‘Book of our land’), a historical-geographical textbook for primary schools, which was published in 1875 and then printed in continual new editions until the Second World War. The conservative, nationalist-religious ideology that was formed here played a key role right up until Finland’s defeat in the war against the Soviet Union in 1944.

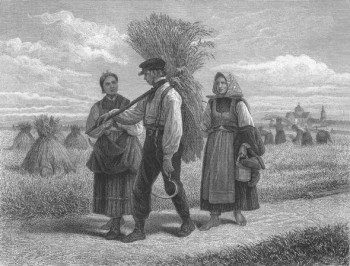

Country people from Vasa area. Adolf von Becker (1831–1909)

En resa i Finland is a textbook aimed at an older readership, published 1872–74. Starting with 36 paintings, reproduced as steel engravings, of Finland’s nature and people, Topelius portrays his view of the country and its people in short essays. (Svenska litteratursällskapet [The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland] has now published the text in a new critical edition as a part of their publication series entitled Zacharias Topelius Skrifter, and it is available in digital form, in Swedish and in Finnish, among other works by Topelius.)

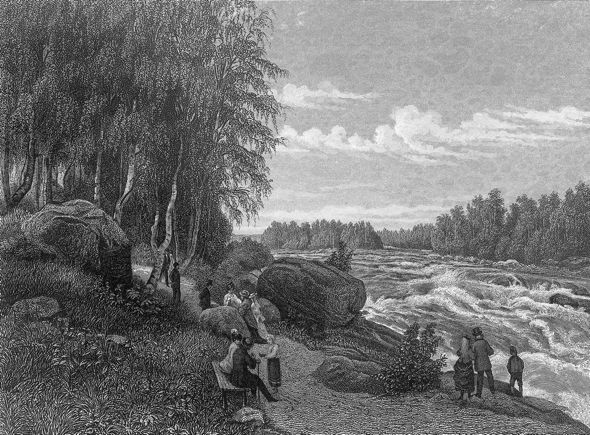

With the skill of an experienced storyteller, Topelius spins dramatic, often anthropomorphic anecdotes of the statistical tableaus, such as when the upper reaches of Imatra rapids become a tale of morality:

’The three moments in a drama – guilt, fall and reconciliation – are clearly distinguishable in nature’s great dramatic poem. Here the artist has portrayed the first moment, guilt. The stream has made its first channel from a quiet lake, thrown, like a human life, between rapids and calm water. He has grown familiar with his power in the upper reaches of the torrents; he is a young titan, foaming with a desire to excel in the struggle for life, to break his way through the walls of mountains and, shrouded in honour, reach the unknown sea.

‘He defies everything, he does not know that nature’s law of gravity will overpower him and that he, in the moment of victory itself, shall be split into atoms of foam. Here he represents her, the selfish power, who believes in herself alone, unaware that she stands under the influence of a higher power, which binds her and has already traced her path and fate. Blind to the irresistible destiny, dragging her into the deep, although she feels a vague sense of unease.

The beginning of the Imatra rapids. B.A. Lindholm (1841–1914)

(–) ‘Even the greatest among the giants of history – Alexander, Caesar, Napoleon I – have, on the night before their fall, been crushed by these harrowing, disharmonious waves in the hidden depths of the soul, and their actions have borne witness to their inner struggle. They have conquered this presentiment as if it were a flaw, they have fearlessly moved on, like Imatra, and perished against the bank.’

An evening on Aura river, Turku. Hjalmar Munsterhjelm (1840–1905)

From an art history point of view, the time was well chosen for such a work. Finland had its first generation of eminent artists at the junction between the Düsseldorf school and the French En plein air, and they are represented here by names such as Hjalmar Munsterhjelm and Berndt Lindholm.

It is a rural Finland that stands out, completely in accordance with Topelius’ interpretation. The cities and the new industries disappear amongst mountains and forests, country people in their national dress are for ever engaged in salting fish and slash-and-burn cultivation of the forest.

Topelius’ prediction that western European civilisation would eventually penetrate Russia via Finland caused scandal at the time, nor did it go down well in St Petersburg. Judging by En resa i Finland, the Russians need not have worried: for the time being there were more lakes and forests than civilisation in the great Russian empire’s little north-western backwater.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Tags: art, cultural history, Finnish history, literary history

No comments for this entry yet