Wo/men at war

9 February 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

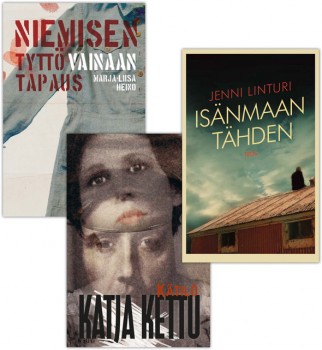

The wars that Finland fought 70 years and a couple of generations ago continue to be a subject of fiction. Last year saw the appearance of three novels set during the years of the Continuation War (1941–44), written by Marja-Liisa Heino, Katja Kettu and Jenni Linturi

The wars that Finland fought 70 years and a couple of generations ago continue to be a subject of fiction. Last year saw the appearance of three novels set during the years of the Continuation War (1941–44), written by Marja-Liisa Heino, Katja Kettu and Jenni Linturi

In reviews of Finnish books published this past autumn, young women writers’ portraits of war were pigeonholed time and again as a ‘category’ of their own. This gendered observation has been a source of annoyance to the writers themselves.

Jenni Linturi, for instance, refused to ruminate on the impact of her sex on her debut novel Isänmaan tähden (‘For the fatherland’, Teos), which describes the war through the Waffen-SS Finnish volunteer units and the men who joined them [1,200 Finnish soldiers were recruited in 1941, and they formed a battalion, Finnische Freiwilligen Battaillon der Waffen-SS].

The work received a well-deserved Finlandia Prize nomination. Tiring of questions from the press about ‘young women and war’, Linturi (born 1979) was moved to speculate that some critics’ praise had been misapplied due to her sex. The situation is an apt reflection of the waves of modern feminism and the reasoning of the so-called third generation of feminists, who reject gender-limited points of view on principle.

Luckily, Linturi is mistaken about the intentions of the critics who praised her – and she has lapsed into a classic feminine underestimation of her own work. Linturi’s novel is one of the most interesting debut works in quite some time.

Extracts from Isänmaan tähden by Jenni Linturi:

Ratas Engineering, April 9, 1941

Antti pressed down on the door handle, felt the bulges of gold, pushed, and stepped inside. Parquet in a mosaic pattern, precisely bordered squares. Table legs casting shadows over them. Everything else was bright. Antti rubbed his hands on his pants and looked up warily. The man ahead of him was still standing in the middle of the room. A thin German doctor placed a stethoscope on the man’s chest. He winced. From where he stood at the door Antti could smell the uncertainty, the hope, the expectation, the fear, the touch of the cold instrument on skin. He looked away. Fear was a weakness between gods and men. It wasn’t something Antti wanted to watch.

Two tables on opposite sides of the room. A Prussian god had descended onto one of them – blond hair, pale eyes, white teeth, sun-toasted skin. A cigarette leaned against the edge of an ashtray and pushed blue smoke into the air. Antti tried to smile. Then he looked away again. He was old enough to know that a god doesn’t look on humans with love or hate, but only with self-interest, as an image of his own success or failure…. A Finnish man was sitting next to them.

‘Tell him to open his mouth,’ the thin doctor said.

‘Hey, man, did you hear him?’ the Finn said. ‘The doctor wants to know why you’re joining. A thirst for adventure? Emotional reasons, perhaps? What do you think?’

The young man looked at the interpreter. A shadow moved over his temple, covered his reddening cheeks.

‘Why do they want to know that?’

‘Look at the doctor. I’m just the go-between.’

The young man turned his gaze to the doctor. The shadow disappeared from his temple. Light lifted the fuzz on his cheeks. That’s when people are at their most naked, without shadow.

‘Nicht möglich,’ the doctor said, walking over to where the god was sitting and grabbing the cigarette from the ashtray with two fingers. ‘Tell him we can’t take him.’

‘Did you hear that, man?’ the interpreter, a petty officer, said.

Antti quickly looked away, at the window, his own feet, the corners, the angles, the houseplants. He didn’t know how to stop looking although he knew it would be better to hold his head as still as possible. When he and Kaarlo had measured themselves according to Gustaf Retzius’s instructions the distance between the back of their heads and their foreheads was two centimeters short of belonging to the master race.

‘You’re perfectly healthy,’ the interpreter continued. ‘But they thought of something. They can’t take you. They wish you a pleasant summer.’

‘But…’

‘They’re discerning men, these Germans. Next.’

Antti stepped forward. For a moment he toed the line on the floor, next to the man that preceded him….

‘And who are you, young man?’

‘Permission slip and genealogy,’ the petty officer translated. ‘And give me the name of whoever referred you.’

‘Major Riekki,’ Antti answered and laid his permission slip on the other side of the line.

The doctor rubbed his cigarette in the ashtray.

‘They want to see your dick,’ the interpreter said. ‘But you probably already knew that.’

Antti tugged at his belt buckle two times before the prong came out of its hole. His pants dropped loosely to the floor. He stepped aside. His socks looked stupid. They made his legs look shorter. There was a hole at the big toe. Why did it always tear at the same spot? He looked up and fixed his gaze on the yellow roses on the back wall. Strange hands ran over his skin. The doctor’s thick hair was combed into waves. His hair tonic smelled strange, cool, like the open sea. There was a yellow streak across the nail of his index finger, just like Antti’s father, a chain-smoker.

‘That about does it.’

Antti stooped to pick up his pants.

‘Aren’t they going to take me?’ he asked the interpreter, then translated it himself into German. ‘Nicht?’

Constricted vowels, strong consonants. Antti stared at the Prussian god, concentrating on not averting his eyes. That’s what bravery is made of, after all – your deeds.

‘Are they going to take me?’

‘Based on this, yes. They’ll still have to look at your genealogical information. You’ll get the final approval by post. If you don’t hear from them, you’ve been rejected.’

Antti clicked his heels together – it felt like the thing to do, to mark the occasion somehow.

‘Danke schön, Herr Führer.’

‘Herr Führer, is it? Listen to that, Franz!’

The Prussian god’s laugh followed Antti to the door. The next man was waiting his turn. Antti nodded at him. They were both there for the same reason, for the fatherland. It made his spirit ring. Antti turned once more to look at the men lined up, waiting. He raised his arm in the air.

It was not the sex of the author that aroused interest but rather the intense, stream of consciousness character portrait and the novel’s taboo subject matter: the comradeship of Finns and Germans in combat and the weight of guilt that this framing of the war engenders. Isänmaan tähden melds events from the war years with those of the present into a nightmarish trauma in the mind of an aged veteran suffering from memory loss. Alongside him is the voice of one of the men who fought beside him, whose heroic stories lose their luster in the reassessment of memory.

A tight connection to silenced history pervades Kätilö (‘The midwife’, WSOY), Katja Kettu’s third novel, which is set in what is known as the Lapp War of 1944–45. Just as portraits of the Finnish Waffen-SS are rare, descriptions of wartime events in northern Finland have been limited to brief chapters in novels. Not many Finns have a thorough knowledge of these final phases of the Second World War. As Kettu (born 1978) puts it: ‘They say that Finland fought its own separate war alongside the Germans. In actuality, Finland surrendered all of its northern territory to Germany. Well, it’s just not a pleasant thought – Finland, an ally of Nazi Germany.’

In Kätilö, Kettu cultivates that alliance through a personal, romantic relationship: a Finnish healer from a family of shamans who works as a midwife falls madly in love with Johann/Johannes, a Nazi officer with German-Finnish roots. Relationships between Finnish women and German soldiers have been a topic of interest in documentaries and elsewhere in recent years. To this day the shame of these women doesn’t seem to have faded, and their stories are tinged with the same guilt as that of the men who joined the SS.

Like Linturi’s novel, Kätilö is based on careful micro-historical research. Both authors have not only immersed themselves in the history of the war but also interviewed elderly people who lived through the events of that time as well as using private letters, diaries and memoirs as sources. The book also strongly follows a vein of women’s history – the chaos of war seen from the point of view of daily, civilian life.

The title of the book fractures into a grotesque allegory as the main character follows the man she loves to the Titovka prison camp in Petsamo [Pechengsky District, by the Barents Sea, northwest of the Kola Peninsula, which was a part of Finland from 1920 to 1944: the Germans used it as a staging area for the attack on Murmansk in the Soviet Union] and is transformed from a midwife who brings children into the world into a prisoner of a shocking industry of suffering who aborts the fetuses of pregnant women for use in Nazi research.

Extracts from Kätilö by Katja Kettu:

Dead Man’s Fjord, 1944

I am a midwife, by the grace of God, and I am writing these lines to you, Johannes. Our Omnipotent God in His wisdom has given me, of all people, the ability to bestow life for some and destroy life for others. In my life drowned in the fire of this world I have given others both life and death, and I don’t know if the course of my life is the result of the drum beat of our times or if our Lord has intended this for me from the beginning. My abilities are my cross and my salvation, my burden and my sentence, and they have sent my life down a wandering path far from my home, and from you, my beloved….

I have left my position in the service of the Third Reich and given up a fleshly life to settle my account with the Lord. And now I can finally take up this pen made from a bullet that has been laying next to my bound notebook for days now….

I know you’re here somewhere, Johannes. You may be lying in a truck, a prisoner of the Russians, your eyes gouged from their sockets, or starving in one of these gullies, with a white fox gnawing at your ankle, but you’re alive. I can feel it. In this world of cripples and sinners I can be blamed for many things, but not for lack of love. And I hope that these lines will reveal to myself as well how a lowly Red pup of the village idiot’s bitch became the Angel of the Third Reich and bedwarmer to the dreaded SS Oversturmführer, and how I ended up at Titovka Sub-camp 322 castrating stallions and doing the work of an Angel of Death.

June: Titovka Camp, 1944

The village of barracks was surrounded by three metres of barbed wire. Signs marked with a skull read in faulty Finnish: ‘Halt! Feeding prisoner of war is forbiden.’

We were met by a high-ranking officer. I was surprised at how beautiful his face was. A graceful, aristocratic nose and long eyelashes. The evening breeze fluttered against his jodhpurs and made them billow like sails. Fragrant spirea grew at the corners of the barracks

‘SS Obersturmführer Herman Gödel,’ he said by way of introduction, and bowed to kiss my hand. ‘We’ve been expecting you, Fräulein Schwester!’ I liked him immediately.

Herman Gödel started to show me the camp as an honoured guest. I was trying to understand from his speech what went where. I had never been in a prison camp before, although a lot of people from Petsamo had, no doubt. I knew that Jouni had created a false past for me, told them that I had worked in several stockades on the isthmus. I was trying to concentrate so that I wouldn’t seem inexperienced. I could see for myself that there were raised towers and search lights at all four corners of the camp.

‘That way we can see if our little lady tries to escape,’ Herman Gödel teased, and I blushed.

The towers aside, the modernity and orderliness of the camp felt reassuring. There was a phone and electrical centre, a notched log wash house, food and weapons warehouses, and a largish building with a sign over the whitewashed door that read: Operation Kuhstall. It was separated by its own barbed wire fence. It had to be the sick room. Everything was orderly and peaceful, not at all frightening, as I had expected. Mosquitoes sang in the grass. Near the sick room cabin, a dragonfly was chasing a horsefly through the air. No hordes of starving Russians wandering among the barracks with their tongues hanging out. Instead there were a couple of trusted prisoners hauling a kettle of soup into a house for the soldiers and prisoners locked within its walls…

I smelled it more than heard it when you came up beside me.

Heart, be still!

I cast my eyes downward and touched my teeth. I had scrubbed them with charcoal to make them shine. That’s when I saw your shamelessly clean boots and lifted my eyes. I couldn’t let you think me a coward….

Herman Gödel assured me I would enjoy the camp, especially now that most of the nurses had left. There was only one Finn left, the head nurse. It was a pity. Finns were such good workers.

‘We have to get the Finns to stay. That’s why we think of you more as a guest of the Third Reich than as an employee.’

I looked around. There was a row of frames set on the lace tablecloth along the back of the table. Generations of Finns sporting lockets and bowler hats stared out of them – precious, trusting. I wasn’t going to be nabbed by any paratroopers here. The two of you blew smoke rings at the red-shaded lamp, which the generator fed a crackling light.

‘Johann and I are old fighting comrades. Childhood friends, in fact.’

‘That is so, Fräulein Schwester. Our mothers went to the same butcher.’

That made me like Herman Gödel even more.

The title character of Kätilö is ostracised from her own community, she is the ‘red bastard’. This ideological chasm of the Finnish Civil War of 1918 – the reds versus the whites – also forms an important blueprint for Niemisen tyttövainaan tapaus (‘The case of the Nieminen’s dead daughter’, WSOY), Marja-Liisa Heino’s fourth novel. It also depicts a war in which very young people of divergent backgrounds are forced to make choices in a world over which they have little influence.

Heino’s novel is a thriller: a young policeman who suffered combat wounds investigates the murder of a young woman who worked in the women’s auxiliary. The book is set in the Tampere region in 1941–42, during the Continuation War, and peopled by the young reds’ resistance movement, the national police, the patriotic auxiliary women, and the Russian prisoners of war who are at first suspected of the crime. Heino (born 1969) also has a micro-historical view of the war: she describes the home front, the everyday squalor of a prison camp, and the hard work of the auxiliary women handling the dead and wounded. The novel is also an excellent stylistic example of narrative based in an old dialect.

Extracts from Niemisen tyttövainaan tapaus by Marja-Liisa Heino (the narrator here is Olavi Nieminen, the socialist father of the dead young woman):

It’s not a workman’s job, making war. You could already see it coming ten years ago, there was so much bluster and preparation going on. Those duffers from the village put up cardboard targets over there at the edge of the woods and blasted away at them. The next farmer over asked me to come, and I think that over the heads of our sons he asked me to bring them over as well. At times like these we really ought to forget our differences of opinion, no matter what side we’ve been on. They’re all buried and gone now, big fights and big fighters. My missus’ brother’s boy was hiding a uniform and some old gun among his junk and sneaking off to train with the fascist guards, claiming he’d been out on the town courting. Course he got that out of his system. Me and my brother-in-law got it out for him. When you’re working a saw for ten hours and only get paid for eight, now that’s a war. That’s what they call a war for liberation – to liberate the working people of this country from every last human right they have. The Social Democrats were taken to the civil guard and minister Tanner stood up on a platform and reviewed the troops – the man was like a radish, red on the outside and white on the inside. I went to our district office and slapped my membership book on the desk and said, here’s one number you can take off your marching list. Told them if Tanner goes to Moscow to negotiate, he’s not going to come back with any agreement. And he didn’t. Hitler didn’t deny that he was itching to attack, but the idiots just didn’t want to believe it. They didn’t believe it until Poland collapsed, skinned alive in a couple of weeks. And there Joe Stalin was, dividing up the spoils, those mortal enemies suddenly the best of friends. Joking with each other about one thing and another. There was nothing surprising about that. The big think in big ways, and they demand that the small give up their rights. The gentlefolk cried for a little while about the villas they had to give up on the Karelian Isthmus, and before you knew it the Germans were here. There was a fellow I knew from the village who was a loader at Siitama station lumber warehouse. That was where he saw the Gerries for the first time, at least a thousand of them waiting to be transferred, standing in line to wash up at the well, and the gals from the village had to go through a crowd of naked men if they wanted to pick up a newspaper from the post train. The loader I knew cursing ‘cause the whole yard was full of the Gerries’ shit. But it didn’t look like the fighting was going very well for them up north. Even my neighbour admitted that the whole war thing seemed to be going badly for the Gerries.

I should have taught the girl better how to use the gun. Yeah, I’m the one who bought her the gun, for God’s sake. They put her right in among the enemy, and they didn’t even give her a gun. I remember one girl from around here, back in nineteen eighteen, she was the forest lookout’s daughter. She could shoot a rifle better than many men could. And those hags spit on her when they took her out to be excecuted. That’s what those rightists were like, pious hypocrites… I bought the gun through an ad in the newspaper when she was threatening to leave. She didn’t go right away though… She’d been working in the Voima cafeteria and she liked it, so she tried to get posted to some canteen job, but they wouldn’t take her. So she ended up with the horses… But first they put her to work up north in a Gerry hospital.

The Gerries didn’t make her serve them long before they transferred her out of there. It was when they ordered her to sing for them. There was somebody from the women‘s auxiliary there who sang hymns for the Finnish boys and the Gerries got the idea that our girl ought to sing to them. So finally she said she would sing for them, and she did for a long time – and when she finished up with the Internationale, the Gerries could tell what it was she had been singing for them. So they didn’t ask her to sing again, and she got sent to the horse hospital. I reckon they thought that was a punishment for her, but she was like a pike in a lake up there, ‘cause she and I used to go and watch the neighbour’s horses ever since she was a little thing. When our Ruska came back all skittish from that first fracas, it was Helvi that he let get hold of him. Even now, whenever you get to the smallest clearing, Ruska will run for cover, as far as it takes to get to the woods. That’s where he learned that. Horses are a lot smarter critters than humans are.

More than the authors’ sex, the significant factor in these three novels are their use of themes heretofore overlooked by histories of the war – themes of Finland’s wartime relationship to Germany, German soldiers in Finland, and the ideologically fractured home front of the Continuation War.

In the narrative methods used the authors are also powerfully contemporary writers: their thriller-like plots disclose their stories slowly, withholding secrets from their reader, who is then required to work out the rich tones and viewpoints of the worlds described. All three books also use micro-historical material in the portrayal of the history of states of mind, building their characters in a way that speaks to the reader.

Translated by Lola Rogers

Tags: Finnish history, Finnish society, novel

3 comments:

4 March 2012 on 8:49 am

Dear Katja Kettu

Congratulating for the Runeberg Prize for fiction awarded this year to you for your novel , Kätilö (‘The midwife’, WSOY).

Nihad A. Rasheed

Novelist , translator , and free-lance journalist

25 May 2014 on 2:17 am

Where can I purchase the book called the Midwife by Katja Kettu? I live in California.

26 May 2014 on 5:26 pm

Dear Liisa,

Kätilö (‘Midwife’) by Katja Kettu, has (so far) been translated into French, Swedish, Latvian, Estonian and Norwegian. It should be available in Finnish at https://akateeminen.com (click ‘in English’).

Best, Soila Lehtonen