A light shining

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

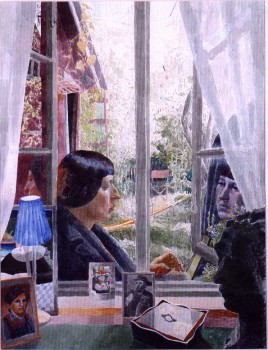

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses.

Soon after that morning, I opened another book, a collection of poems by Saima Harmaja. My mother used to recite to us a few lines from one of the poems, ‘Nuori enkeli’ (‘The young angel’), by way of an evening prayer. But she had never read aloud the stanza that I now read. It is engraved on my memory: ‘How hard was the journey, how bewildered the brain / As one the world spoke, in the language of pain’. I felt I understood what was meant by those words, though at that point I had seen so little.

The third important book of my early childhood was my sister Inari’s first-year reading book, which also taught basic arithmetic. There was a short story in it about a girl who was given six cherries, delicacies I myself had never laid eyes on. The girl was supposed to share the cherries with her sister, but she claimed she had been given only four cherries. She gave two to her sister, and ate up four herself.

To me, this was like a thriller or a horror story. As a five-year-old who had learnt to share everything equally with my sister, I had never read of a more appalling crime. I began to see that there was a difference between right and wrong and that a person needed to learn what the difference was if she wanted to avoid suffering a great deal, and causing others to suffer.

Reading was the most important thing in my life when I was at school. I would never have called it a hobby, though; it was something much greater and more important than that. Going to school was secondary, and that showed in my marks; I was always a poor student, right up until sixth form. A musical child knows early on that she’s in training for her future career, but I had no idea. I wasn’t in training to be a writer; I read for the sheer pleasure of it. Of course, I later understood that it’s only through reading that you learn how to write. And I didn’t feel the need to talk about what I’d read to anyone else; books were too private for that. It is with books, and not people, that I spent the most pleasurable moments of my life.

Around the time I was learning to read, we were given Zacharias Topelius’s Lukemisia lapsille (‘Reader for children’) in a deluxe edition illustrated by Finnish and Swedish artists. I was still reading it when I was at my single-sex secondary school in Helsinki, along with the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen. Andersen is still one of my great role models. It is often said that children need happy endings. Just last summer, I reread Andersen and realised how amazingly often his stories end unhappily, at least in the conventional sense. Children die in them, and so do lovers, and the one who loves the most stays behind, alone. And still the stories provoke hope and insight.

Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, which I was given as a seven-year-old, is still among the books that are most dear to me. Many of the scenes in the book will stay in my mind forever. Some of them are fast-paced and funny, like the japes and scrapes of the conceited Toad. Others possess the pure magic of poetry. For example, the scene in which Mole feels homesick. His abandoned former home sends him a message, which he obeys. There’s also the Water Rat’s wanderlust, the lure of the unknown South, and the words of the wayfaring rat: ‘I will linger, and look back; and at last I will surely see you coming, eager and light-hearted, with all the South in your face!’

In his work, Grahame captures the sacredness of experience and the spirit of nature. This places his work in a higher and nobler class of children’s literature – and world literature.

I don’t see a clear difference between writing for children and writing for adults. It’s just that when I write for children, I’m writing for everyone; when I write for adults, I’m only writing for some people. In everything I write, I try to be ‘brief, clear, and rich’, to quote Andersen. The question ‘What is true?’ is fundamental to my life.

During the morning devotions at school, we would often sing: ‘Spirit of truth, guide us’. And in our reading book, we were our told: ‘Child, shun lies, always tell the truth. Always tell the truth, in play and in earnest’. At the beginning of the 20th century, the realists thought you should only write what is true. How can a writer who writes mainly fantasy, or something called sci-fi, abide by such instructions? In my view, it’s not impossible. Art is a game and a lie, but as such, it approaches truth. That’s the paradox of art.

Literary fiction couldn’t exist without imagination or rational thought. In my opinion, the imagination is the basis of all rationality. It is also the basis of conscience. A person needs to be able to imagine the consequences of her actions both for herself and others. Art or literature cannot, then, be separated from moral choices.

Reality, and above all the human world, is made up of impossible connections. Fiction and reality exist in a symbiotic relationship. What could be clearer proof of this than money, which once again has recently betrayed its unstable, ghostly, and fictional nature? It’s quicksand, and something even more deceptive. I’ve termed such phenomena tribars, after the impossible objects devised by the physicist Roger Penrose. A tribar is an image of human reality, which brings together truth and untruth, symbol and matter, rationality and irrationality, to form a construction that is logically impossible.

My books do not exactly take place at a certain time or in a certain place. Like Angelus Silesius, I believe that you are not in a place; rather, the place is in you. I don’t see myself as writing national literature, nor have I ever dreamt of writing the great contemporary novel. I have always wanted to write short books that nonetheless have the spirit of truth in them. National literature was at one time necessary to create a spirit of togetherness for a new state, and a collective symbolism, but I believe that it has had its day. It is sometimes said that all good literature is political. Maybe so, but then good literature is also always cosmopolitan.

It cannot be denied, however, that place shapes people in powerful ways, since memories are of course anchored in place and time. Place, time, and language are the foundations of identity. Of necessity, a writer draws on her own life experiences when writing, even if they are not obviously apparent in her books. All of one’s personal history, all of one’s life experience – and that includes what one has read – are there in the writing. You don’t have to go and write about things you haven’t personally had contact with – but I use ‘personally’ in a very wide sense. Still, writing is for me a forgetting of the self – the individual abandoning herself to the greater sum of things. In writing you go back and forth between private and public zones. You can only relate the most private things publicly, and in a common language.

I think of world literature as both shared and indivisible. Children’s literature is also world literature. All literature involves sharing and reciprocity, giving and receiving gifts. All works, whether they are written for children or adults, in whatever language and country, form one and same world literature, in which all works exist in relation to each other. Completely autonomous works don’t exist, and every book has many authors, both dead and alive. Literature is intellectual capital that is not used up or diminished through distribution.

The first obligation of the writer is to write as well as possible. In fact, thinking about it, that is the writer’s only obligation.

Translated by Emily Jeremiah

Tags: books for young people, children's books, fantasy, Finnish Weird, science fiction, writing

1 comment:

Trackbacks/Pingbacks:

-

Differences Between Writing For Children and Adults - Slap Happy Larry

6 December 2018 on 6:14 am[…] Leena Krohn: I don’t see a clear difference between writing for children and writing for adults. […]

9 August 2011 on 8:38 pm

Finnish-Canadian artist Marja-Leena Rathje gave me a link to this excerpt after I told her that a photograph of hers (a flower with stamens-tower and little ascending and descending insects) reminded me of “Tainaron.” I like this piece very much–it is so congenial in what it says of books for children, transformation, gifts, and more.

http://www.marlyyoumans.com