Stories in the stone

2 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

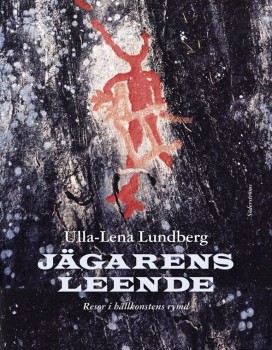

Extracts from Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010)

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘I think about this often – I who love painting but who still chose a career that involves me sitting and hammering away, day in and day out, like a true rock-carver,’ writes author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg in her new book on the art of the primeval man

When the children of Israel went into Babylonian captivity, hanging up their harps on the willow-trees and weeping as they remembered Zion, my sister and I were already sitting by the rivers of Babylon. We knew how they felt. Our father was dead and we had been sent away from our home. We sat there clinging to each other, or rather I was the one clinging to Gunilla, and she had to try to rouse herself and find something for us to do, to give us something else to think about.

‘Come and look!’ she would say. And I would go and look, because I wanted so much to be distracted, to be a bit happier. When my father died I had only just begun to talk. His death put a stop to that, and we had to start from the beginning again. Gunilla taught me what everything in the world was called, and when I got a bit older she knew the answers to all my whys and hows. Everything I knew I had learned from Gunilla. She had arrived in the world fully-formed, whereas I was a wet, shapeless lump that needed serious work if it was ever to amount to anything. My sister loyally shouldered that responsibility.

Long afterwards, when she was already seriously ill, she read Martin Andersen Nexø’s memoirs. She related how he had been forced to drag his little sister around with him throughout his childhood. Tears came to my eyes.

‘And that’s just what you had to do too!’ I said.

She looked at me kindly.

‘No,’ she said. ‘That was different.’

‘Different how?’

‘Because you were the one who was my sister,’ she said.

That’s certainly one way of looking at it, because there may well be some compensation to be had from someone who believes in you unquestioningly and who agrees to everything you suggest. Everything Gunilla liked I liked too. It was fortunate for me that she was an intellectual, deeply interested in nature and culture. Thanks to her, I didn’t have to make any time-consuming detours before working out where my own inclinations lay.

We shared each other’s experiences, and, because there were two of us, we were a bit braver, a bit more adventurous, than if we had each been alone. As a child I was always scared: without Gunilla I would hardly have dared move. But together we ventured out into the world, me slightly behind her, but still able to see what was going on. It was a good position in which to grow up and muster courage. And I learned an incredible amount; thanks to Gunilla, I had a two-year head-start in many different areas.

The great advantage when I started school was that it meant Gunilla could borrow twice as many books. I was too shy and timid to pick out a single book for myself from the school library, but Gunilla borrowed books for both of us, taking half of them out on my card. Then we would walk home with the books in our school-bags, scarcely able to contain ourselves until we could start reading. Our cheeks glowing, we would lie on the floor, each of us reading a book, and then, when we had finished, we would swap with each other.

During the summer we would go on geographic expeditions in the rowing boat, and learn to identify birds and plants. It was quite natural that archaeology – what we called ‘in the olden days’ – became one of our great interests. We spent our earliest years on the site of the medieval Franciscan monastery on the island of Kökar. Not far from there is the recently excavated Bronze-Age dwelling of Otterböte. In Granboda, where our grandfather lived, Iron-Age burial sites exist alongside the current settlement. Our mother grew up on the heavy clay soil of Gammelgård in Esbo, on what had been the seabed during the Stone Age. Someone once dropped a stone axe in the sea, and it turned up in the middle of one of our fields.

All the while that you take an interest in various things, learning and talking, thinking and fantasising about them, you calm down and start to imagine what your future life might be like. As adults we lived in different places, but stayed best friends and were in very regular contact. Gunilla became a librarian and, after her years in Africa, married and settled in England, a country we had got to know from Enid Blyton as a magical place riddled with secret passageways and full of tinned food. In reality it consists of layer upon layer of archaeology and history, wherever you look. Every one of my visits to Gunilla involved prehistoric sites, an abiding shared interest.

For my part, I wrote and read and travelled and imagined that my life would always be like that. You go through life as best you can, first on healthy legs, then suddenly one day with a limp in your left leg and a terrible back. Sitting down is difficult, lying down is difficult: from experience I know that the princess in the fairy-tale with the pea in her bed suffered from a slipped disc. Long journeys and ambitious clambering were no longer feasible. It was time for comfortable and well-organised archaeological trips in Europe, and I spent the following years working my way through the great Ice-Age caves in the South of Europe armed with a stick and a supporting corset, with Gunilla at my side.

Doing sensible things gives you time to get well again, and over time I was almost back to normal. We could revert to making our own expeditions, and were hopeful that this would continue for a good while yet. But towards the end of 2002 Gunilla was diagnosed with multiple system atrophy, a name which describes exactly what the disease involves. In a very short time she was badly disabled, and Nigel Kelly, her husband, and I started to organise wheelchair trips. Two months before she died we travelled to Brittany, for a successful exploration of the great mystery left by the region’s prehistoric inhabitants in the form of processional roads and barrows. We managed to get all the way out to the island of Gavrinis and inside the magnificent passage grave with its richly ornamented stonework, not only a grave but a centre of the universe.

There we stood on the edge, unafraid. She was having trouble talking by this time, I was the one calling ‘Come and look!’, just as she had taught me to look at the world around me when we were young. In Gavrinis we had reached a conclusion – complicated, unintelligible. No answer, but a vast space for insight and farewells.

Gavrinis

Do you think the grave is too deep?

From now on I will be evaluating archaeological sites according to the wheelchair principle. If I can manage to push a wheelchair then the site is okay. If not, then it’s useless.

Carnac is okay. We’ve reached April 2005, and Gunilla is confined to a wheelchair. And I, who so want to give her the wings of the morning, walk behind and push, or hold her under the arms for the short stretches that she can walk. It is what it is, in other words, a thoroughly successful trip, and the one which turned out to be her last….

We reach Roscoff, then there is a car trip down through Brittany, an astonishingly wild and beautiful landscape with mountains, vast areas of heathland, the smell of herbs, and, in the south-east, Carnac, the central point of an extensive and spatially arranged sacred landscape which has no equivalent in modern architecture. We stay at a B&B just outside the town, owned by a true Breton, where we have a whole little floor to ourselves and are served magnificent breakfasts. We’ve never stayed anywhere as nice as this on our travels, and the three of us often forget how ill Gunilla is: we’re on one of our usual archaeological trips, making the most of everything we see….

We manage to see a deeply satisfying number of ancient monuments in Carnac, both the big, official ones that indicate the presence of a central authority out of all proportion to the relatively modest population of farmers and fishermen who lived in the area, and quite a number of almost private burial mounds, some small stone circles and some standing stones that seem to have had a more local function. The whole chronology of Carnac is anchored in the Stone Age: no metal tools were used here. Even so, immense stone projects were undertaken, projects that few people would have seen completed in their lifetime. Here long-term planning was combined with the short perspective of individual lives. How did this society really fit together? Who had the necessary oversight, the authority for this sort of all-encompassing central planning, stretching over several generations? How could the immense outlay of labour be justified among people who were relatively short-lived? Something drove them to it. Religious devotion? Slave drivers? Priests, seers and oracles who were convinced it was necessary to ensure the continuation of our wretched existence on earth?

I admit that I find it easier to understand cave art and art on rock-faces and under overhangs than the predominantly abstract art associated with vast stone projects like grave chambers and processional roads. Maybe the explanation is simply that I am happy to imagine myself painting, and even carving, but I could never break my back on these insane stone-shifting projects.

I was hoping that Gavrinis might supply some answers. It is a huge passage grave, on an island outside Larmor-Baden, where an entire landscape has been constructed around the meticulously carved stone walls of the burial chamber. During the Neolithic Age the sea-level was a good deal lower than today, which meant that Gavrinis was part of the mainland and thus connected to the many stone monuments and barrows of Locmariaquer, across the Auray River.

It is by no means certain that we are even going to get there, and we nervously check the weather and timetables. A small pleasure boat takes visitors to the island, and if they say there’s no space for a wheelchair then we’re finished. We didn’t check beforehand, so that they couldn’t say no in advance. But everything goes well on the quayside. The wheelchair folds flat and Gunilla is light as a feather. It’s nice being out at sea, and we get the chance to see the Er Lannic stone circle, half visible above the water, a good illustration of how much higher the sea-level is today. It acts as a reminder of the fact that many less spectacular ancient sites, like the foundations of huts and other secular constructions, have been lost to the sea.

In those days Gavrinis was perched even higher than it is today, but pushing the wheelchair up the gravel track is still tough. But then we are there, confronted with a multi-layered mystery. It has been dated to approximately 3500 BCE, slightly older than Newgrange and Knowth [County Meath, Ireland], but it had an even shorter life than Newgrange: after just five hundred years, around 3000 BCE, the entrance was blocked off. The corridor was filled with stones, a wooden construction in front of the entrance was burned down, and the whole façade was covered with rocks, soil and sand. After that the site was abandoned, another sign that is simply isn’t possible to talk about a single culture, or even any continuity in the way religion was practiced, during the 3000 years or so that the area functioned as a sacred landscape.

In later times grave-robbers broke into the burial chamber from outside. It was empty when restoration work began in 1979. Compared with the vast size of the mound, 50 metres in diameter and seven metres high, the chamber itself is tiny, just 4 x 4 metres, while the corridor leading to it is 17 metres long. If it was a burial chamber, was it reserved for a single ruling family and then sealed when the family’s time was over? We have no idea; but we stand and blink like moles at the ornamentation which stands out, neatly carved and confident, on the large stone-blocks that form the walls of the corridor and its only slightly wider culmination, the chamber itself. The blocks are stone, but look like clay: tight circles stand out, as though they were made by a finger running round and round through considerably softer material.

They look almost like massively enlarged fingerprints, but naturally have another function. Among all these roundels and half-roundels there are also bordering areas of ornamentation and other types of decoration: elegantly plaited bands, snakelike zigzag patterns, and very delicately carved narrow, pointed stone axes. And yes, up on the ceiling, on the underside of the massive block of stone that covers the whole chamber, the oxen with great horns taken from one of the megaliths in Locmariaquer. And, tucked in among the larger blocks forming the walls, a smaller stone with a carving of an axe with a handle which probably also comes from one of the stones there.

The concentration of all these carvings, largely non-figurative or stylised, makes an overwhelming impression, as if all the artistic skill of Carnac were concentrated here, below ground. It looks incredibly organised and calculated – yet at the same time there are small incongruous elements that suggest haste and even sloppiness.

How else do we explain why five of the wall-stones in the corridor are undecorated, and why a couple of them aren’t completely covered in engravings? Some of the stones were carved on site, others made elsewhere and brought here already decorated. Not to mention the fact that they made use of the megaliths at Locmariaquer to get hold of the massive roof stone with its engraved image. The opening to the passage faces southeast, but not so that the sun ever reaches the passage or the chamber; maybe this was never the intention, and Newgrange is the exception, but it could also be a mistake.

Somehow you get a sense of terrible haste, as if the foreman was running late and was trying desperately to get everything finished so as not to come to a premature end himself. Ancient sites usually make a tranquil impression, but at Gavrinis it is as if one is witnessing the arrival of haste into the world. The more you hurry, the more things go wrong, and the more time you need to put it right. In the end the foreman stands there breathing shallowly at the entrance, telling the torch-bearers not to light up certain places during the inauguration.

And after those hints of crisis, the calmness of the art itself shines through. These stones have stood facing one another for five thousand years, in deep darkness, absorbed in their twisting lines and skeins, and now they emerge into the light, as vivid as skin, as fresh as if the hand that carved and engraved them had brushed the dust off them and given them a satisfied pat only a short while ago.

Life is short, art long – it gets no clearer than that. But that is no reason for us to be disheartened, because the hand behind the art is our own. Gunilla and I stand in Gavrinis happy and triumphant. ‘We made it!’ we say. It’s hard work getting out again, and the wheelchair leaves deep tracks on the damp ground on the way down to the boat. There are several passengers in it, one going farther than the rest of us. From a distance it isn’t possible to see either my happiness at having had her in my life, or my sorrow that I can’t pull her back from her approaching death. It is things like this that art deals with, and it is in this arena that we leave our mark.

Translated by Neil Smith

More on Gavrinis at http://www.culture.gouv.fr/fr/arcnat/megalithes/en/index_en.html

Tags: art, cultural history, history, travel

No comments for this entry yet